Very few, if any, are truly self-sufficient these days. That is to say, we don’t typically build or produce things for ourselves; rather, we rely on a network of producers and service providers to help us get through our day to day lives and perform many critical tasks and functions. Another name for this reliance is a dependency, and much like we have come to rely on certain services to achieve the outcomes we desire, similar types of dependencies exist in the software engineering world, and those dependencies have to be made available by some mechanism generally called Dependency Injection, and that is what I’d like to discuss today.

What is Dependency Injection?

Dependency Injection or DI is generally thought to be a very complex topic, but in truth, it’s quite simple and easy to understand, even if you’re five, as this example illustrates:

How to explain dependency injection to a 5-year-old?

When you go and get things out of the refrigerator for yourself, you can cause problems. You might leave the door open, you might get something Mommy or Daddy doesn’t want you to have. You might even be looking for something we don’t even have or which has expired.

What you should be doing is stating a need, “I need something to drink with lunch,” and then we will make sure you have something when you sit down to eat.

Source: StackOverflow

DI is a technique under the Inversion of Control (IoC) principle/pattern. In this mechanism, a centralized object is made responsible for providing all the services or things on which our application blocks depend. The application blocks define the list of services or items they need, and they don’t have to worry about how to construct or instantiate those services and how to dispose of them if they’re no longer required.

Angular’s Implementation of DI

In the Angular framework, DI is one of the core mechanisms, taking care of instantiating and loading dependencies for all components, directives, and services.

Angular automatically creates a centralized Injector that is loaded when the application bootstraps. This Angular injector looks for all defined dependencies and maintains instances that can be reused, inside a container, generally referred to as DI Container.

But how does the injector know how to load or create an instance of a dependency? Angular has something called Provider, which “provides” that information to the injector. When you require a dependency, be it a service, function, or value in your application, you have to register a provider in the application injector. The injector will then use that registered information to instantiate and load the dependency whenever it is required.

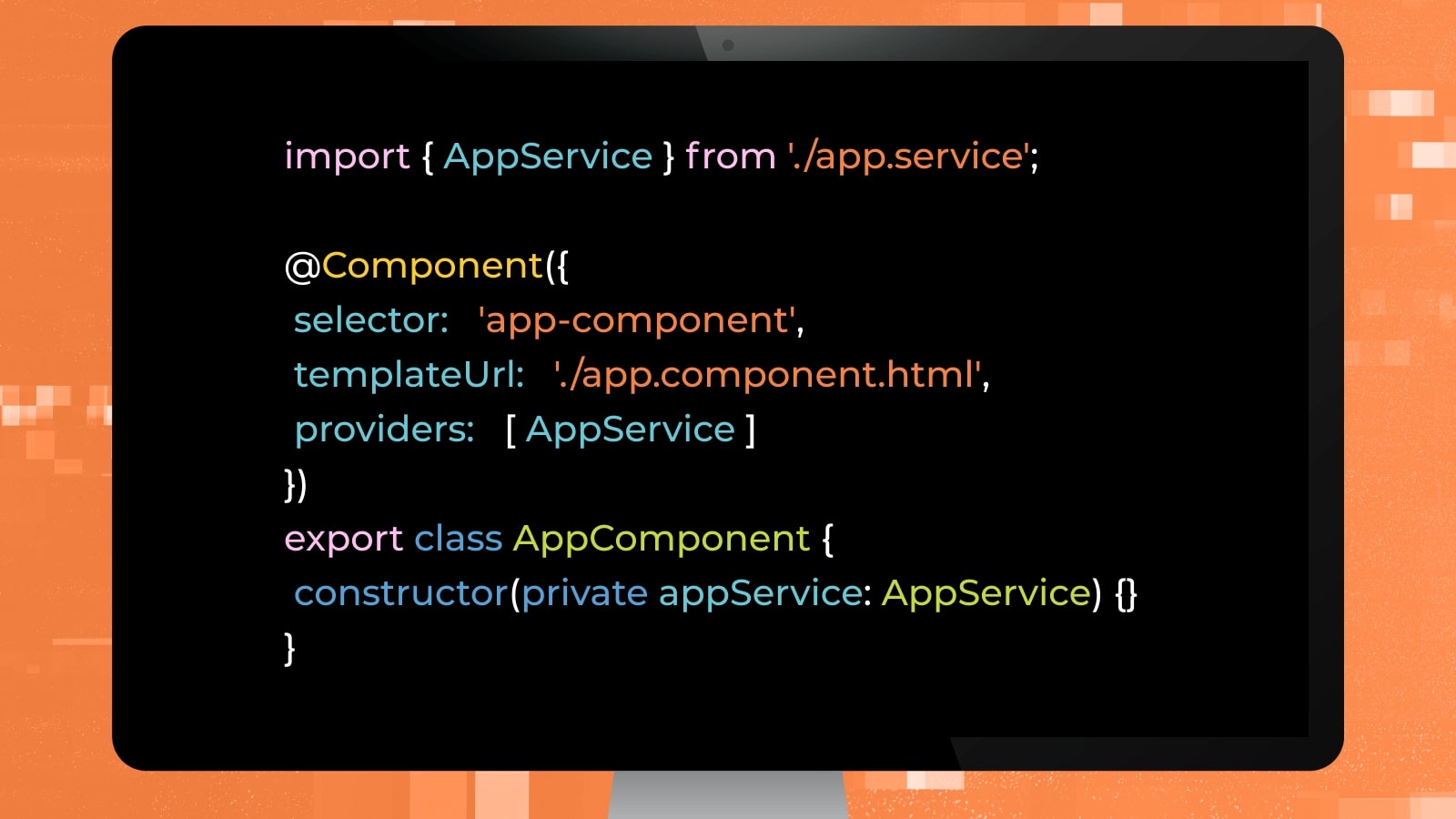

Considering the constructor here, as soon as code reaches a point to instantiate this component class, it informs Angular about the dependency. The Angular process checks if the injector has an existing instance of dependency. This dependency injection in angular looks for an existing instance in its container and creates one if not, and finally returns the instance to Angular by keeping a reference in the container.

Note: The type of dependency is NOT optional, you have to tell Angular about the object type so it can create its instance when needed. In this example it’s the AppService type.

In this example, we have only one dependency, whereas, in practice, it can be more. When Angular finally receives the instances of all the dependencies from the injector, it then calls the constructor with those service instances as arguments, of course, in the same sequence.

There is a small caveat in this example; we provided the service reference to Angular using the component’s providers’ collection. If we use this approach, we are telling Angular to get a new instance of the AppService for each instance of the component. But that probably isn’t what we needed, right?

Hierarchical Injector

The Angular’s root or centralized injector is a hierarchical injector, which is one of its most exciting features.

It means if we provide a service for one module or component, the instance of that service will be available to all the descendants of that module or component. In an Angular application, there are multiple places where we can “provide” a service:

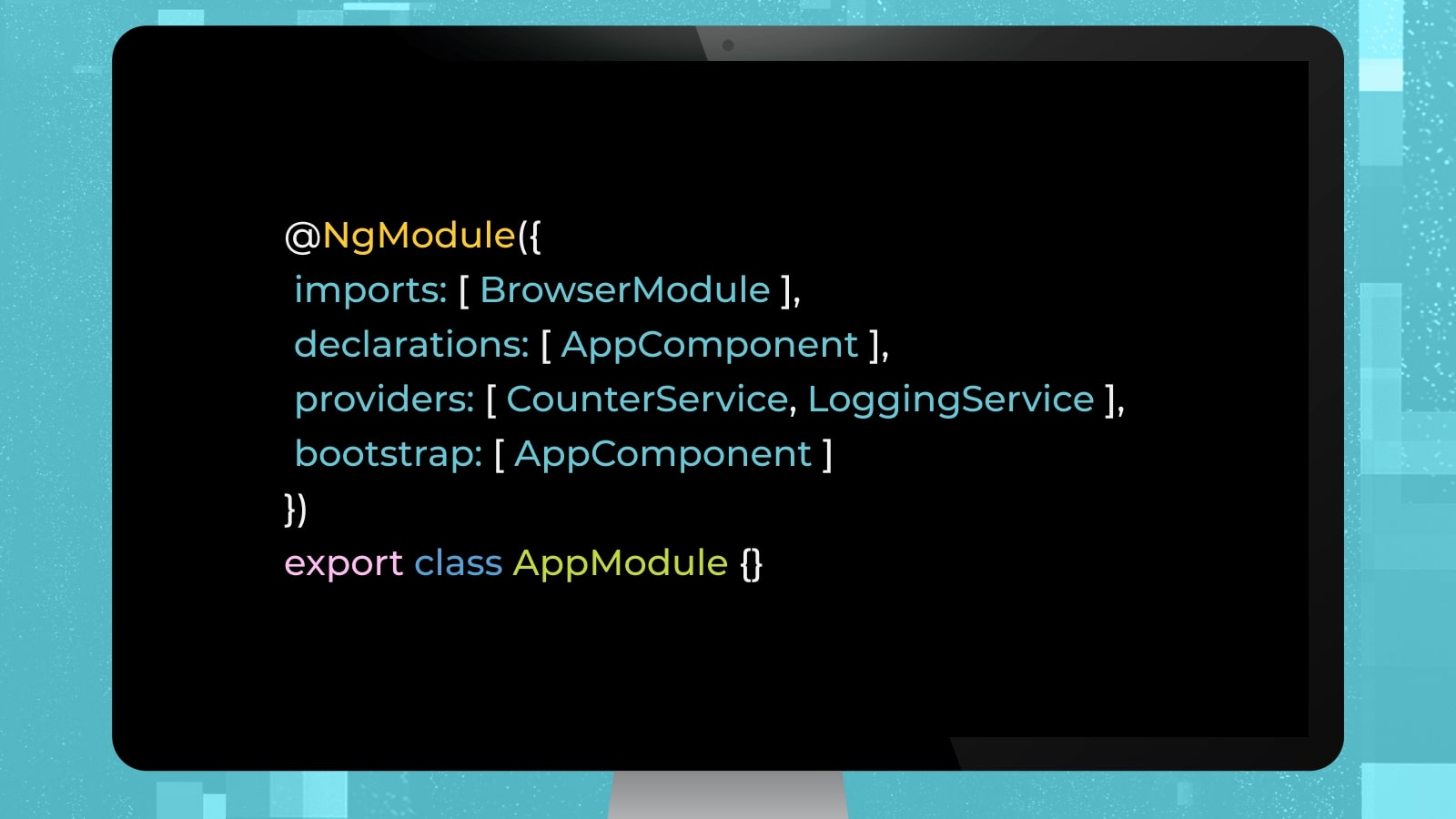

AppModule: If we provide a service at this level, it will act as a Singleton service, i.e., one instance for the whole application, unless we override this for a sub-module or component.

AnyOtherSubModule: If we provide services at this level, Angular will create a child injector automatically, which will inherit from the parent injector. This child injector will be responsible for maintaining instances of the services provided for this module and all its children (modules, components, directives, services, etc.) unless we override this in a sub-module or component.

AppComponent: Providing a service at this level means one instance of service is available for AppComponent and all its children, but not other services or AppModule. Angular will again create a child injector inherited from parent injector to maintain instances of services at the AppComponent level.

AnyOtherSubComponent: As in the example above, one instance of service will be available for one set of instances of this component and it’s children (if they exist). This will also be handled by an automatically created child injector for each instance of the component.

Note: None of these patterns are wrong. It will vary depending on the application needs and whether you want one Singleton instance of a service or you want separate instances of the service for each component and its descendants.

In real-world applications, most of them will have child injectors being created by Angular to manage service instances and provide them whenever needed. Since Angular creates these child injectors automatically, Angular handles all the clean up as well when those child injectors are no longer required.

The @Injectable Decorator

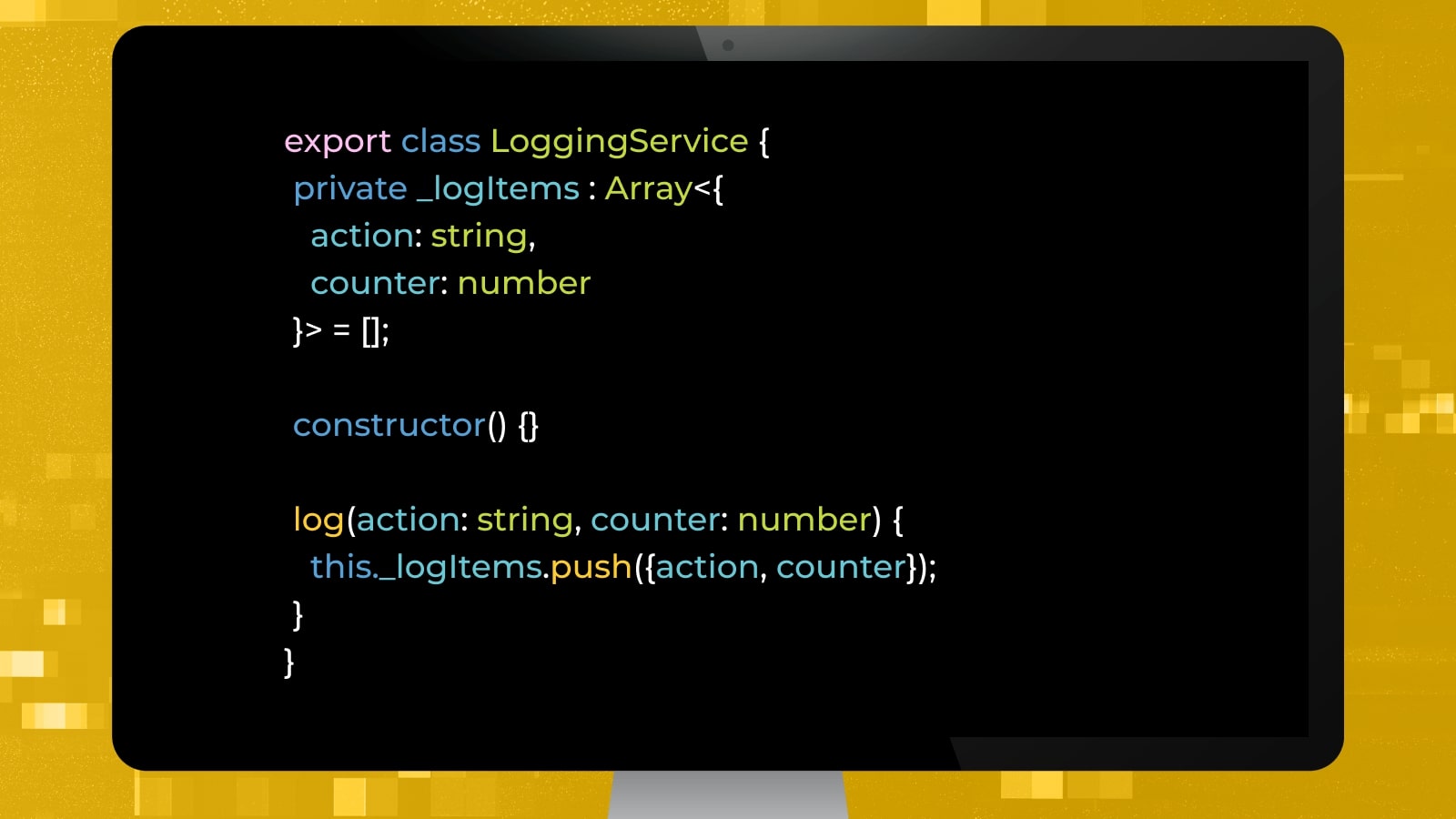

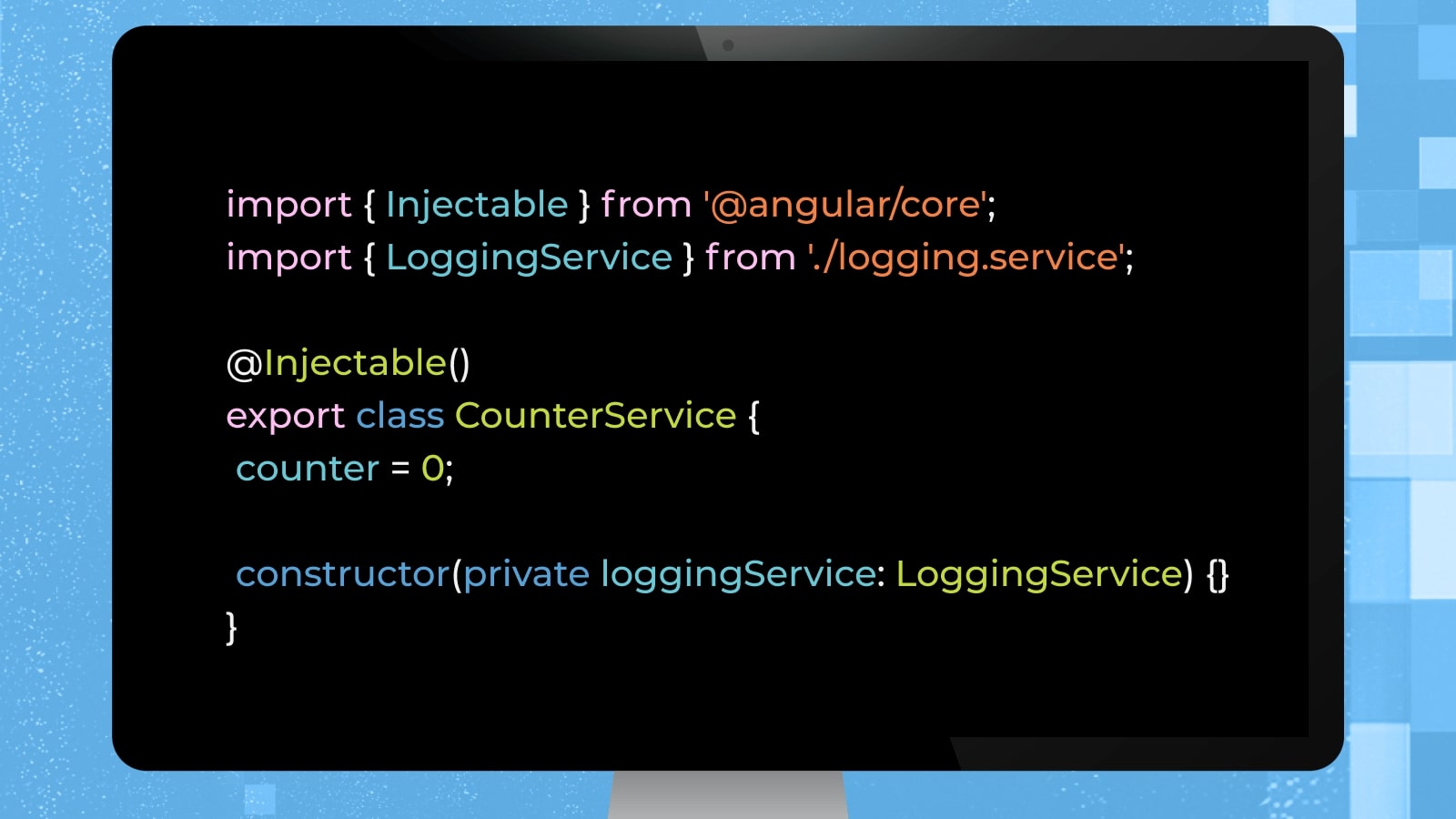

We’ve talked about injecting services into components, directives, and pipes, etc., but haven’t talked about injecting services into services. Look at the example below and guess if it has an error:

There is a problem in the example above and Angular will report an error similar to the one below:

The class ‘CounterService’ cannot be created via dependency injection, as it does not have an Angular decorator. This will result in an error at runtime.

Either add the @Injectable() decorator to ‘CounterService’, or configure a different provider (such as a provider with ‘useFactory’).

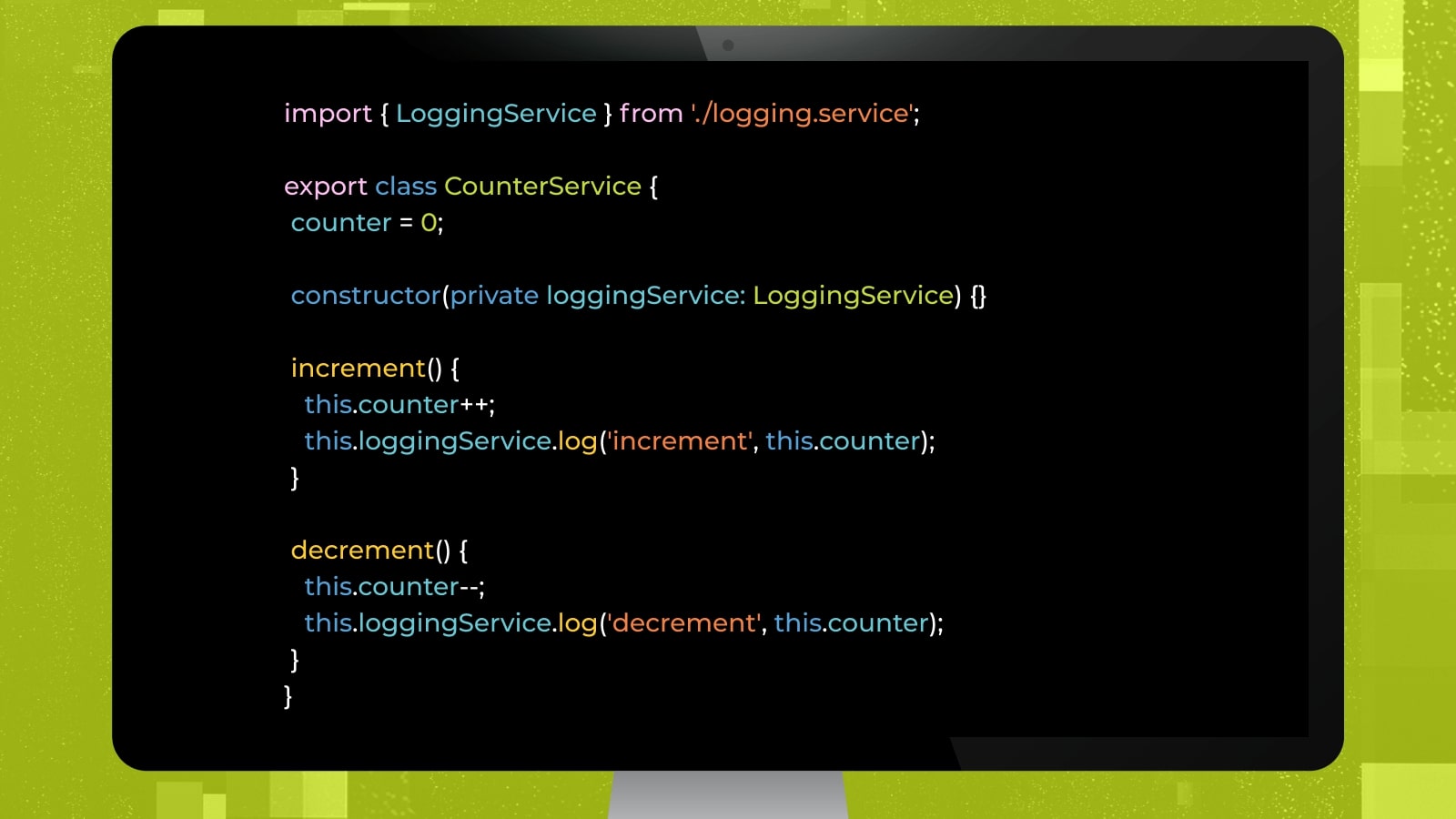

This is a very common misconception about the @Injectable decorator. Since the CounterService depends on the LoggingService, we have to tell Angular that CounterService is “injectable”, which means it depends on some other service and that other service will be injected “into” this service. So we have to add the @Injectable decorator before the CounterService declaration like below.

The important thing to note here is that no error was reported for LoggingService because it doesn’t depend on anything for instantiation.

For the sake of performance, consistency, and avoiding any future errors, it’s a best practice to add @Injectable decorator to all service classes. For instance, if we decide to inject some dependency in the LoggingService in the future and forget the @Injectable decorator, Angular will throw the same error.

To fix the above error, simply add the @Injectable decorator to the CounterService class.

The Super Power of the @Injectable Decorator

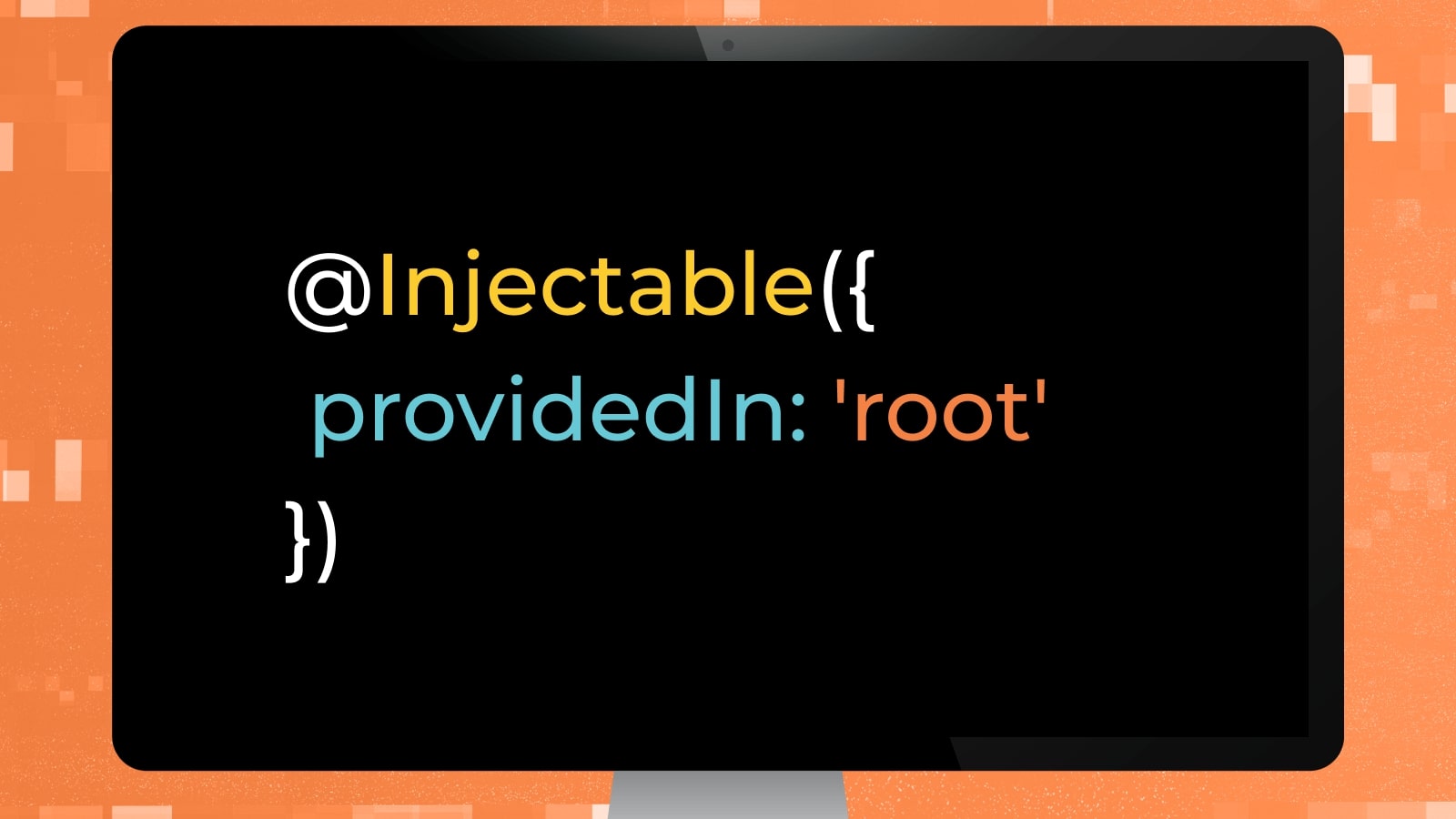

The amazing @Injectable decorator has another fascinating usage. We can use it to provide a service at the root injector level, which makes this service globally accessible to all modules, services, components, pipes, etc. No matter where your service resides in the code, you can make it globally accessible by passing in a special object to the @Injectable decorator like below:

Voila! Our service is now globally accessible and can be injected into other modules, services, and components without providing it anywhere else. And one very important benefit that we get here is that our service is now fully tree-shakable.

By default, Angular CLI generates services with this pattern and recommends having @Injectable decorator being added to all the services. As mentioned earlier, it’s a best practice to have it with all service classes, but it is up to the application requirements and use cases to choose for other available options and patterns.

As of Angular 9, the Angular team introduced two more value options for the `providedIn` property, listed below:

‘platform’: Since we can have multiple Angular applications running on one page, for instance, if you have a micro frontend architecture, you can share services across applications using this value.

‘any’: Use this value to instruct Angular to create a global instance of this service for all eagerly loaded modules, and a separate instance of this service for all lazy loaded modules that inject it.

Take Away

In this article, we saw how Dependency Injection works in an Angular application and how we can utilize the injectors and providers to get instances of our services based on our requirements. However, this topic is broad and I have only skimmed the surface. But I hope that my simplistic approach was able to provide you with a broad understanding of Angular DI and inspired you to consider it for your next development.

The example code for this article is attached for download here.